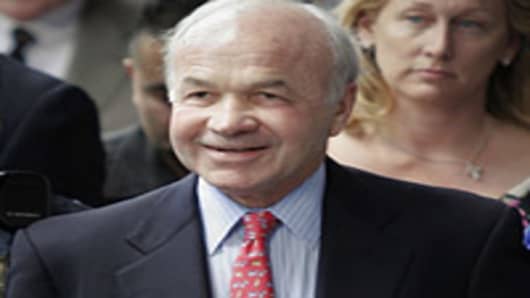

LLANO, TX – When Enron filed for bankruptcy on December 2, 2001—at the time the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history—the once high-flying energy company cemented its reputation as the very symbol of corporate fraud.

Its top executives, including Chairman Ken Lay, CEO Jeffrey Skilling and Chief Financial Officer Andy Fastow became household names, and the term “Enron accounting” joined the business and political lexicons.

Eventually, dozens of high-profile convictions and some tough corporate reforms later, the public moved on.

But on a sprawling, picturesque ranch here in the Texas hill country outside Austin, F. Scott Yeager can’t move on. Not yet.

“I try to put behind me, I try to go on with life,” Yeager said in an exclusive interview. “But the part that keeps taking me back, let's call it, the injustice anger part.”

After years of silence, Yeager agreed to speak to CNBC in hopes of changing the widespread public perceptions about Enron and the sweeping federal investigation that followed. He was one of dozens of executives ensnared in that probe, but in 2009 became one of the only ones cleared of criminal charges, in a case that went all the way to the Supreme Court. He has left the bustle of Houston and moved to the ranch in Llano, where he does consulting.

But rather than be content having cleared his own name, he wants to clear Enron’s name as well.

“I think that the perception—and I'll call it the Enron myth—is very solidified in the country,” he said. “And it is definitely incorrect and inaccurate.”

Yeager, 60, is one a small but increasingly vocal group of ex-Enron employees still trying to rewrite the legacy of Enron, ten years after the firm’s epic collapse.

He was a top executive at Enron Broadband Services (EBS)—a tiny division, but one that prosecutors claimed was a prime example Enron’s fraud. They accused executives of misleading investors by over-hyping the division’s prospects at the height of the technology bubble.

Yeager, who helped develop many of the unit’s products in the 1990s, was accused of conspiracy and insider trading for selling stock with the knowledge that the technology being touted to investors didn’t actually work.

“Yes, it did work,” he said. “In multiple ways.”

Prosecutors claimed Enron did not yet have the software it would need to run its broadband network, but Yeager said it did.

“I was in New York, and saw it work. I was in San Francisco and saw it work. I personally used streaming media. So I know it worked.”

He still holds onto hundreds of computer files and video demonstrations that he says are proof Enron was not a fraud, but a pioneer in many technologies that are commonplace today.

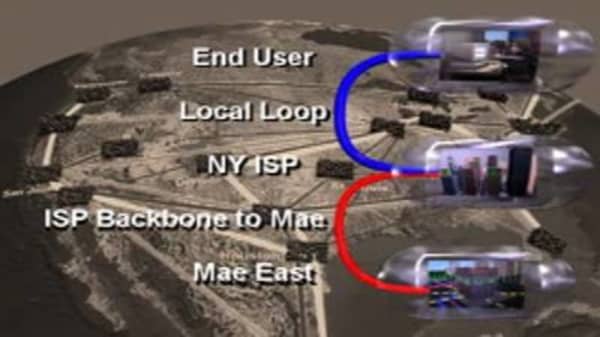

One demonstration from 1999 narrated by Yeager appears to show an early concept of cloud computing, in which a user could access online applications or “apps” through an Enron network.

“You would ride across the Enron ‘cloud’ all the way to the source of the content,” the video says.

“We drew everything as a cloud back then,” Yeager said. “We didn’t coin it. But the notion of cloud computing as a bunch of servers distributing inside of networks—the internet—and that you would get services from them close to where you are physically, we did come up with that idea.”

Another video from 2000 shows an early concept of video conferencing. “Enron Communications is changing how the world communicates,” the video says.

And yet another presentation from 2000 includes a demonstration of an on-demand movie service similar to those available on most cable TV systems today:

“Once the end user selects the movie, it takes just a second for the video stream to begin,” the demonstration says.

Enron's Former Executive Vice President of HR

Enron had a deal with Blockbuster to provide movies on demand, but prosecutors claimed Enron over-hyped the prospects for the venture, and underplayed licensing issues with Hollywood studios.

Five Enron Broadband executives ultimately pleaded guilty to reduced charges, but Yeager says all were pressured by prosecutors.

“There were tens of thousands of really good employees, honest people, top people that were very proud to work for Enron that worked very hard on all kinds of innovative things of which EBS, our group, was just one of those,” Yeager said.

“It was a great company. It was an exciting company,” said Cindy Olson, Enron’s former Executive Vice President of Human Resources.

Olson instantly became part of Enron lore when investigators uncovered video of her answering questions at an employee meeting in 1999, the year before Enron’s stock price hit its peak.

“Should we invest all of our 401k in Enron stock? Absolutely,” Olson says, the room erupting in laughter as Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay look on.

“Everybody burst out laughing. I mean, it was a joke,” says Olson, now 59 and living in Colorado. “Never in a million years did I think that one little second of being humorous or flippant would turn into investment advice.”

Nonetheless, Olson found herself testifying before Congress and questioned by the Department of Labor about the 401k plan following Enron’s collapse. She also testified in defense of Chairman Ken Lay at his 2006 criminal trial.

“I was proud to work for Ken Lay,” she said. “You know, I dealt with a lot of CEOs in Houston, and Ken Lay was the best.”

Olson wrote a book about her experiences, The Whole Truth So Help Me God (Tate Publishing & Enterprises, 2008), that is being re-released this month to coincide with the tenth anniversary of Enron’s bankruptcy.

“I want to talk,” she said. “I want to talk about what a great company it was.”

She is not alone.

Olson is prominent in a web site, ungagged.net, created by Houston video producer Beth Stier and purporting to tell “the other side of the Enron story.”

As an outside contractor who handled Enron’s corporate video production, Stier was the official custodian of thousands of hours of videotape. As a result, she found herself at the heart of the investigations of Enron, and, she says, under unrelenting pressure from federal prosecutors.

“Not one of the Enron defendants got a fair trial because of vicious and deliberate prosecutorial abuse,” she said. “During the Enron trials, I experienced it myself and I also saw it happen to many other people with my own eyes.”

Allegations of misconduct on the part of prosecutors have been raised in a number of Enron-related cases, some still pending. But officials have always insisted their actions were above board.

The site, which Stier calls a “webumentary,” includes dozens of interviews with former Enron employees, attorneys and legal experts detailing what it was like to be on the inside of the Enron scandal. Ironically, the site uses some of the internet video technology Enron helped develop.

“Politically, I knew the case was driven to indictment,” says Lay’s defense attorney Mike Ramsey in an interview on the site. “I think many of us who were reasonably sophisticated in the law knew that. Ken never was willing to believe that.”

Lay, the politically connected founder of Enron, was convicted on six securities fraud counts and four bank fraud counts in 2006, but the convictions were wiped out when Lay died before he was able to appeal.

A former assistant to Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling says on the site that FBI agents tried to intimidate her colleagues.

“I mean, the FBI is acting like the KGB for heaven’s sake in this case,” says Sherri Sera. “And they were given carte blanche to do it.”

Skilling, now five years into a 24-year prison sentence for conspiracy, fraud and insider trading, is continuing to appeal his convictions, including a new petition to the Supreme Court just this week. Neither Skilling nor his legal team are involved in the “ungagged” web site.

Leslie Caldwell, the first director of the Justice Department’s Enron Task Force, discounts the web site’s central theme that the Enron prosecution was politically motivated and aimed at a solid company that had suffered a “run on the bank.”

“There was absolutely no political pressure to get indictments or to not get indictments,” said Caldwell, who left the task force following the 2004 indictment of Jeff Skilling, and is now a partner at Morgan Lewis in New York.

“There definitely was a lot of pressure, but the pressure that we felt as a team and as professional prosecutors really was let’s make sure we get this right.” Caldwell is confident they did.

“I know there were a lot of really good, solid, talented people who worked at Enron,” she said. “But it was not a run on the bank.”

The problems occurred, she said, when Enron decided to move beyond its roots as a pipeline company and expand into more risky ventures like energy trading. By the time investors and counterparties began abandoning the company in 2000, she says, the die was already cast.

“They were a company that was teetering and that was basically counting on its continued rise in its stock price for its survival.”

Even Cindy Olson, the former human resources chief who worked at Enron from the time it was founded in 1985, acknowledges that by the time Enron reached its peak, the company had somewhat lost its way.

“We didn’t require that some of the upper management people live the values of integrity, respect, communication,” she said. “And I think that’s what happened. I don’t think we were true to our values.”

Those values are laid out in a 1998 corporate video featuring Lay and Skilling entitled Enron Vision and Values. “There probably are times that there’s a desire to cut corners,” Skilling says. “We can’t have that at Enron.”

“Enron is a company that deals with everyone with absolute integrity,” Lay adds. “We play by all the rules.”

Follow Scott Cohn on Twitter: @ScottCohnCNBC